Ice Therapy For Horses

By Siun Griffin, Equine Physiotherapist and LCAO Community Manager

Using ice or cold water on horses for injuries is nothing new. But it certainly has become more sophisticated in the past 10 years.

Cold therapy not only helps treat existing injuries but it can also be used to aid recovery and reduce soreness.

Why is it used, when is it used, and how does it work?

The Main Purpose Of Ice Therapy For Horses

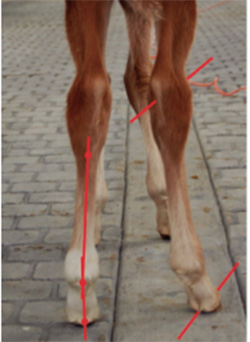

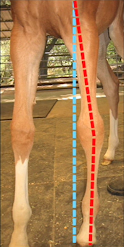

In simple terms, using ice or cold water helps reduce swelling and inflammation. It can also slow down the inflammation process and reduce the damage it causes to tissues.

Reducing swelling and inflammation will help lessen any pain your horse is experiencing from its injury. And, of course, the cold will help remove heat from the affected area.

Key effects of ice of cold:

- Reduce swelling

- Slow or reduce inflammation

- Restrict blood flow

- Pain relief

- Reduce heat

Is Ice or Cold Water Better

Ice or ice water is always better than just cold water. Generally, water from the hose is not cold enough. However, if that’s your only option, then it is better than nothing.

We’ve all been there – standing holding the hose as we let cold water run over a leg for several minutes!

Thankfully, today we have products designed to apply ice to horses more easily than with a hose or convincing a horse to stand in a bucket of ice water.

Of course, with a little creativity, you can put together your own DIY ice wraps in a few minutes. More on that in a minute.

When To Use Cold Therapy

Rick Mitchell, DVM, MRCVS, Dipl. ACVSMR, of Fairfield Equine Associates in Newtown, CT says, “If you are presented with an acutely swollen, hot limb, ice is never an inappropriate initial therapy.”

It is pretty hard to go wrong when deciding to apply cold to an injury or suspected sore spot on your horse. However, you need to make sure you do it correctly. More on that in a minute.

When in doubt, always ask your vet if icing is ok for your horse. While, in most cases, icing will cause no problems, there are some contraindications.

Dr. Brendan Furlong, MVB, MRCVS, of B. W. Furlong and Associates ice, is contraindicated for the following:

- The skin is broken

- Possible infection at the site of the injury

- There is a laceration to part of the hoof

- If water softens a hoof injury area, it could make it worse

- Take extra caution when using ice on young horses and foals as they have thinner skin, which can freeze more quickly

How To Use Ice Therapy

Whichever way you decide to use ice or cold therapy on your horse, there are a few simple rules you need to follow.

Always ice for 20 minutes and no longer than 30 minutes at a time. There are two exceptions to this rule. For some acute injuries, it is better to ice for only 10 minutes with 20-minute breaks and frequent repetitions.

Icing for over 30 minutes will cause a rebound effect in which the horse’s body sends a rush of blood to the area negating the effect of the cold. Your ice will also ‘warm’ up, no longer being effective.

You also want to limit the time to prevent damage to the skin. Leave at least 30 minutes between icing sessions.

The other big exception to icing time is for laminitis or when the horse seems to be on the verge of developing it. One of the main treatment protocols in these cases is to ice the feet. The longer, the better, as it will help reduce the onset of laminitis or reduce the severity.

Icing Precautions and Tips

To protect the skin, always place something, like a thin towel, between the ice and the skin. The cold therapy will be more effective if you wet this towel in advance.

Methods To Ice Your Horse

The old-fashioned ways to apply cold therapy are cold hosing or filling a bucket with water and ice. These are, of course, still useful, but getting a horse to stand in a bucket of ice water doesn’t always go so well!

Today, you can buy specially designed ice boots that allow you to easily apply this treatment. These are great and super easy to use but can be expensive.

For a smaller budget, there are some DIY versions you can make.

Fill ice pop sheets with water or water and some rubbing alcohol and freeze them. The rubbing alcohol will prevent the sheets from completely freezing so you can shape them around your horse’s leg.

Place a wet towel over the area, then your frozen sheet, and secure it with a polo bandage or duct tape.

You can also do something similar with large, sturdy ziplock bags.

One method I really like is ice-cup massage. This is a great way to treat large sore muscles in the body. Partially fill a paper cup with water and freeze it.

When you want to use it, peel off sections of the cup and massage it over the area you want to treat for 10 to 15 minutes. As you are constantly moving, you don’t need a barrier towel.

Final Thoughts

Ice is a wonderful, simple, and inexpensive way to manage your sports horse or include it in injury treatment.

While it can’t completely prevent injury, it can potentially reduce the effects, help with soreness and recovery, and reduce inflammation.

This, combined with veterinary guidance and treatment from your osteopath, physio, or massage therapist, can help your horse stay comfortable and happy.

For more information on how you can become an Equine Osteopath, click here

.png)