It’s the Rider!- Part 2

By Chris Bates, DO and Animal Therapist

Last time in Part One, I introduced you to a case of a horse with recurrent neck problems, and I discovered over my observations and assessments that the causative impact was from the rider/owner.

Of course, this is not an uncommon thing to discover when working with horses. When I worked as a riding instructor, I often saw riders who would explain to me that their horse was “badly behaved” or that they had had numerous therapists and vets out but could never isolate what was causing their horses to play up.

I firmly believe that however clear-headed and open-minded people can be, the human ego is far too strong for people to consider that they might be the problem.

Not to say that people are arrogantly assuming they are perfect, it is simply that they don’t see themselves mirrored in the horse’s physicality.

Osteopathy teaches us that form is a result of a combination of the material present and the afferent inputs upon it. Essentially, anything is a product of its make-up and environment interaction.

This dynamic interplay is ever changeable (luckily) and it shows us exactly what we need to see if we take the time to step back and observe. That really is the key word here, “Observe”. Step back and see and you have moved from where you were, where we only saw part of the whole.

The case I was covering in part 1 was clear if I “stepped back” and saw the whole picture. I had seen the horse ridden but only by the owner’s friend, not her herself.

If you have not yet read part one “It’s the Rider – Part 1”, I recommend you do so to fully appreciate this article.

It is not necessary to be a riding instructor to observe a rider’s impact on the horse. We can use our Osteopathic thinking to consider the forces such as gravity, tensegrity, and momentum and this will give us a good idea of what is happening.

Of course, it is essential to have a high degree of knowledge of anatomy and how the biomechanics of the horse function.

So, what was the rider in part 1 doing?

This particular rider was eager to enhance her flatwork (dressage) and did some light jumping. She used a general-purpose English saddle that was well-fitted.

One clue as to the way she rode was the worn line on the stirrup leathers; the friend I had seen ride had to shorten the stirrups two holes before she rode.

It is quite common for trainers and the advice of other riders to suggest riding longer in the stirrups for a “deep seat” and “better posture”. Unfortunately, many fail to consider the rider’s biomechanics and their level of competence when making these suggestions.

If a rider lacks the independent seat and balance that is required to ride with a longer leg position, they will make other adjustments when attempting to ride with a longer stirrup. These adjustments may give the rider a sense of control and stability (temporarily), however the connection to the horse becomes distorted.

The rider/owner in this case was falling into the trap of trying to run before she could walk. When the rider lacks the ability to connect through the seat effectively, they are actually better off easing themselves into the process by using the support available to them, in this case – slightly shorter stirrups.

Now I’m not suggesting that riders should become dependent upon stirrups and devices to maintain stability; consider a child learning to ride a bike and using stabilizers (training wheels). The experience gained through gradually lengthening stirrups over time allows the rider to develop better balance and proprioception without overburdening the horse.

This rider in particular had gone into what I used to call the “water ski” position. Because the stirrups were too long and the style of the saddle allowed for the leg to swing forward (to accommodate jumping seats), she had stretched her legs forward to seek the stirrups and therefore security.

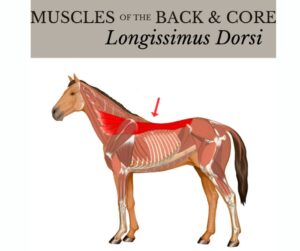

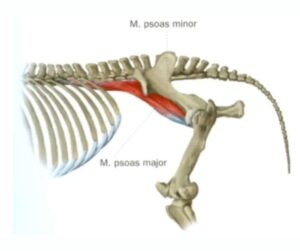

We know in Osteopathy that one thing has to affect the other and of course, this does! In response to her forward leg position, the rider’s pelvis was tucked under too far causing her to straighten and brace her back, this conversely leads to the horse sensing more pressure in movement due to her lack of shock absorption.

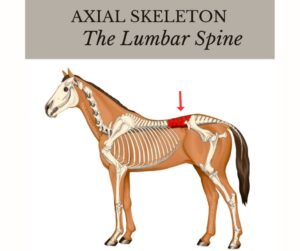

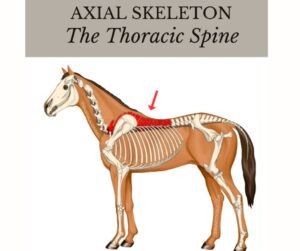

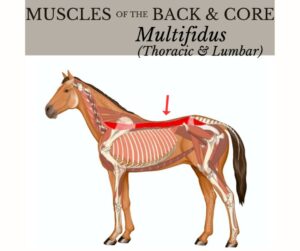

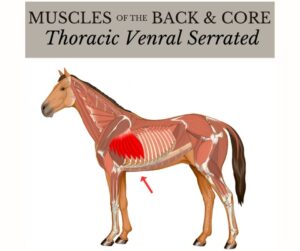

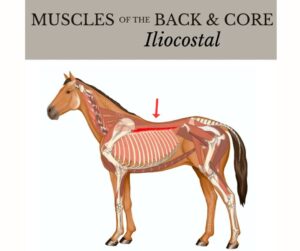

The rider had to counter the forward leg by leaning backward behind the vertical and so distributing her center of gravity over the horse’s lower spine (lower thoracic and lumbar regions).

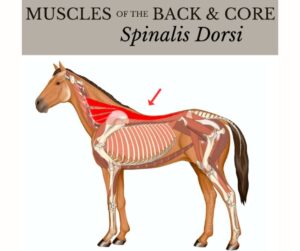

The horse can carry the rider’s weight quite well and without too much compensation when they are sat over the horse’s center of gravity. This is due to the balance being better and the intrinsic stability of the horse’s thoracic region and ribs, large areas of firm connectivity create a strong structure here.

The horse’s centre of gravity (COG) in natural (un-ridden) locomotion is located just caudal (behind) the heart and roughly mid-way between the dorsal and ventral lines. This obviously changes slightly when we mount up and changes again when horses develop to high levels of riding or different disciplines.

Our rider was sitting their weight way behind the COG and so the horse’s threats to the rear were completely understandable as that’s where the weight was going. This is a very common fault in riders and almost always leads to the horse hollowing their back.

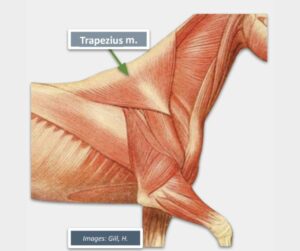

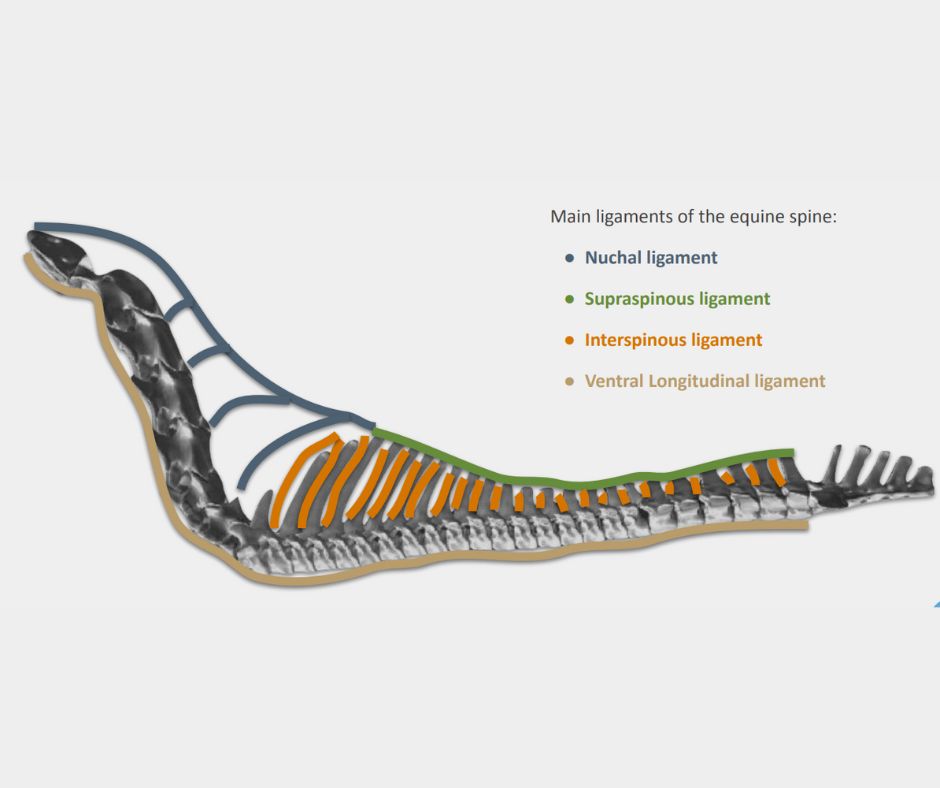

The hyper-extended neck of this particular horse would certainly have been connected to the overall hollowing. However, there is another aspect to consider, the reins.

When this rider was in the “water ski” position as described earlier, the arms would be drawn back with her. This led to her having long reins yet braced and tense. The effect of the rein aid always being “on” meant that the horse was getting mixed signals when asked to move forward.

This is a little like driving the car with the hand brake on. The overuse of contact through the reins in any riding position will lead to altered ways of going in the horse.

The contact is meant to be offered in front of the horse and the energy of movement is pushed into the rein, unfortunately, many riders will bring the contact back to the horse reversing this principle. This can cause jaw tension (TMJ), hollowed back, shortened strides, lack of engagement, and of course, behavioral “issues”.

This particular horse was adding some rotation to his neck to evade the contact being applied. This way he could take hold of the rein and essentially nullify its impact to a degree.

This tilting/rotation is often seen and should be considered as a sign of pain, poor riding, tack fit issues, or even dental problems.

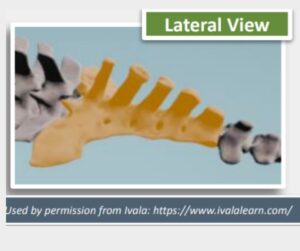

Osteopathically, it was clear to me that this rotation reduced his ability to bend laterally (Fryette’s laws of spinal motion). This coupled movement was what was likely creating the lesion that was recurring time and time again.

So where are they now? Well, the rider took my advice to have some training with the professional I had recommended. This trainer was actually very professional in that she worked with the owner’s current trainer to discuss a plan forward rather than just replace her.

This is obviously a great learning opportunity for the previous trainer and she took this very well. The rider has been attending Pilates classes focused on rider position and has made leaps forward in her riding abilities.

And the horse? He is now moving well, getting stronger and even winning at local dressage competitions. His shape has changed to one much more conducive to ridden work and a healthy spine.

The take-home…

It is very important for any practitioner to understand their limitations. Although I am a qualified trainer and riding instructor, I felt my place was better served as the therapist. Referring to another professional is not a case of losing work, in fact, it’s quite the opposite.

By making the right referrals and creating a network with other professionals, you can become a real hub of knowledge for your patients. Pointing people in the right direction for their animals is often what we as therapists of all kinds do.

The skills and abilities acquired through a course like the LCAO Diploma serve just as much to tell you when not to intervene as when to do so.

Most importantly, our courses give you the philosophical understanding and technical knowledge to see way beyond just the bit where symptoms show. If you treat a cat’s tail, the noise will come out of the mouth, but the mouth isn’t the problem!

My advice? Step back and see more, be open to referrals to other people, ask opinions, and be a detective. It can be so simple when we have much more information, such a huge part of Osteopathy is the examinations, assessment, and development of a hypothesis.

As Andrew Taylor Still himself said, “Keep digging”…

For more information on how you can become an Equine Osteopath, click here