Pain does not always equal damage

Pain does not always equal damage

Chris Bates M.Ost – Registered Osteopath

Whether we are talking about Humans or Animals, pain science is an important subject to understand when we embark on a career in therapy.

In the world of Osteopathy, pain is possibly the most obvious and prevalent sign of something affecting our patients. This doesn’t mean however that the pain is a good indicator of the severity of damage (if any) to the tissues.

Here we will explore the phenomenon we call “Pain” and why it might be misleading in some circumstances.

What is Pain?

It can be hard to put a short definitive answer to this question as pain is variable and depends upon the patient and their personal perception. Physiologically speaking, pain is the electrical impulses via sensory nerves that have been stimulated at nociceptors (Pain receptor nerve endings) being processed in the higher centers of the central nervous system (CNS).

The higher centers of the CNS will process the information and decide if the pain signal requires an action to reduce further damage or create heightened awareness such as a sympathetic response (Fight, flight, fright response).

This makes the science of pain seem simple. One could even ask, “ if it’s like flicking a switch at the receptor, how could the signal be wrong?” That is the question that biomedical scientists have been grappling with for nearly a century.

It’s important to understand pain as it can have hugely detrimental impacts on sufferers both in acute and chronic presentations.

The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (2023) describes how pain has wide-reaching effects such as limiting work abilities, disrupting relationships and social activity, mental health concerns, and rendering daily tasks difficult or impossible.

Within the animal care world, pain has equally far-reaching consequences. Horses that are ridden, driven, and possibly competed can present with performance issues, time out of competition, and worsening behavioral traits.

Dogs may find regular walking activities difficult and consequently end up lacking in general health. For people working with animals in conservation, pain could reduce or inhibit breeding behaviors. Animals in pain will often exhibit “stereotypic” behaviors which are repetitive movements or actions that seem to have no intended goal.

These behaviors can become physically damaging. Horses for example might “crib” and “windsuck”. This can damage teeth, lead to colic, or exacerbate ulcers. Dogs may damage furniture or pace leading to nail and paw injuries or repetitive strain.

Of course, pain in animals can also put owners and handlers (even the public) at risk if the animal’s behavior becomes dangerous.

Does Imaging Help?

Medical and Veterinary science has benefited immensely from the development of various imaging methods such as ultrasound, X-ray, and MRI. There is no doubt that putting as many pieces of the puzzle together as possible is the sensible thing to do when looking to make a diagnosis.

However, many studies of human pathology and radiology have found that a large proportion of positive radiology findings are asymptomatic (pain-free) and many cases of severe pain have no radiological signs to find.

Many of us as pet owners will have experienced taking our beloved animal to the vet only for them to say that there are no obvious signs of damage, injury, or degeneration. So why is this?

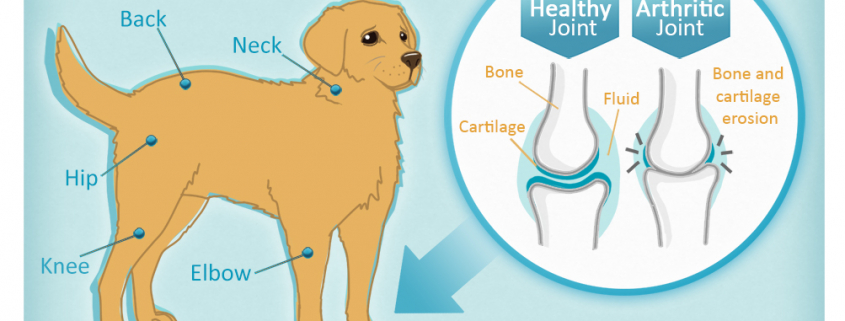

While invaluable, imaging can only show us one aspect of the process of pain. Yes, there are obviously going to be times that osteoarthritis (cartilage degeneration), an osteophyte (bone spurs), or a disc prolapse are visible and match up perfectly with the presenting pain and disability.

The problem with relying too heavily on imaging when assessing pain is that there are other subtle influences on pain severity and location.

Referred Pain.

I often say to my patients, “If you are standing on a cat’s tail, the cat will make a lot of noise, but it’s not where the noise is coming out that the problem lies”.

Ok, this might sound a bit crude and I certainly don’t go around standing on a cat’s tail, but think about the metaphor here. Some dogs such as German Shepard are more prone to hip and lower back dysfunction as they age.

This is often due to the morphology we have bred into them which makes them stand their hind limbs far out behind, extending the hips and leaving the tensegrity of the spine and hind kinetic chain to support gravitational forces.

In Osteopathy we are well aware of how damage, inflammation, and compromised tissues in one location can create symptoms in other locations. If there were to develop a compression at the nerve root due to excessive spinal extension or distortion to the nerve passing the hypertonic psoas muscle then the distal (further from central) reaches of the nerve could display symptoms.

In this case, the area where pain, numbness, or changes in sensation occur wouldn’t actually be where the focus of intervention should be.

There are various ways in which the course of a nerve can be perverted, join our courses to find out how.

Central Sensitization.

When pain does occur as a result of trauma, illness, or another input, the body will react by trying to reduce the effects of the damage and trying to avoid the same thing happening again.

We have reflex actions to quickly get ourselves out of danger that require no conscious control. We develop psychological aversions to situations that caused pain before, this is part of the holistic model of Osteopathy that considers psychological and physical interrelated and inseparable.

Unfortunately, chronic pain or repeated exposure to the stimulus can cause the body to essentially “tune-up” the pain volume dial in our higher centers. This means that it takes less of the stimulus to evoke the pain felt.

This can also mean that sensations that would not normally feel painful become extremely uncomfortable or painful. We call this Hyperalgesia. Imagine a horse who has a vast history of hoof problems and poor care.

This horse may get rescued and begin to receive the right hoof care and trimming but the ground had already been laid for the chronic repeated pain stimulus to “tune-up” sensitivity.

This could make riding on roads difficult, lead to unwanted behaviors, or cause lameness after visits from the farrier.

I tend to describe it to owners with another metaphor. If the nerve is like a path through the forests, a path that gets walked along a lot will be easier to walk down, and a path that is not used so much will become overgrown. A nerve pathway that is stimulated over and over can lead to changes in the processing sensitivity.

Join our courses to find out how Osteopathy can help pathways downregulate again and function better.

Conclusion

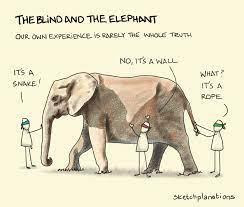

Something we must remember is that the feeling of pain is created within our central nervous system as a way to instruct our conscious mind to take action or avoid action.

It is a signal, not an actual manifestation of the damage (if any) itself. Pain is often not felt in the location of damage, pain is often “up-regulated” beyond what is reasonable for the condition presenting and pain is influenced by other factors such a mental state or vital reserve.

Our work as therapists, Osteopaths or coaches is to educate owners about pain in a way that makes sense to them. By the way, please feel free to use my metaphors. By understanding the science of pain and how to affect it, we take control over what can often feel overwhelming.

Owners often feel completely helpless when caring for an animal who is experiencing pain, especially when that pain seems to not match any damage or conditions. If owners understand that the pain itself is not equal to damage and that there are ways to improve outcomes then it can really help support their care and potentially even save animals from unnecessary euthanasia.

Bibliography:

Harte, S.E., Harris, R.E. and Clauw, D.J. (2018) ‘The neurobiology of central sensitization’, Journal of Applied Biobehavioral Research, 23(2). doi:10.1111/jabr.12137.

Pain (no date) National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Available at: https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/pain#:~:text=What%20is%20pain%3F,%2C%20almost%20unnoticeable%2C%20or%20explosive. (Accessed: 31 October 2023).

Soo, M. and Worth, A. (2014) ‘Canine hip dysplasia: Phenotypic scoring and the role of estimated breeding value analysis’, New Zealand Veterinary Journal, 63(2), pp. 69–78. doi:10.1080/00480169.2014.949893.

What is pain? (no date) What is pain? | British Pain Society. Available at: https://www.britishpainsociety.org/about/what-is-pain/ (Accessed: 01 November 2023).