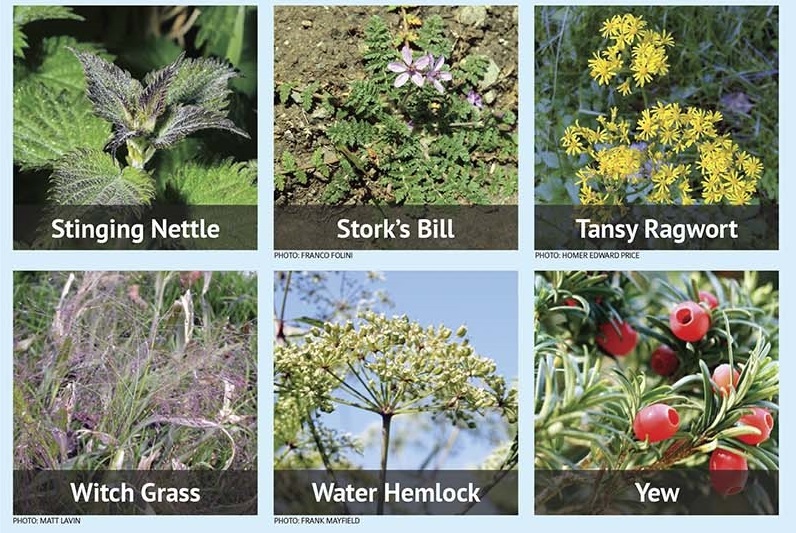

Many plants are toxic for horses to eat, and while some are not appealing to them and they often avoid them, there is still the risk of accidental ingestion.

As a horse owner, it is important to know what plants to look out for and ensure your horse does not have access to them.

This is part one of my series of articles on poisonous plants for horses.

Ragwort

Most horse owners are probably familiar with Ragwort, what it looks like, and its dangerous effects. Due to its bitter taste, horses usually avoid it. However, horses on poor grazing that are hungry might eat it.

It also becomes more appealing to horses when it dries or starts to wilt. It is a slow killer in that its effects are not seen straight away. Eating just 1 kg (2.2 pounds) can cause fatal liver failure.

Ragwort is difficult to manage if it invades your land. Don’t mow or cut it and pull it up from the roots before it flowers. Using herbicides may also be necessary to control it.

Poison Hemlock

There are several varieties of Hemlock, and it is known by a number of different names.

These are just a few:

- Spotted Hemlock

- Poison Parsley

- Nebraska Fern

- California Fern

- Winter Fern

- Wild Carrot

- Cicuta

- Snake Weed

This plant is highly toxic and contains neurotoxins, the most troublesome being Conine. When ingested, symptoms appear quickly, often within 15 minutes but can take 1 to 2 hours.

Any part of the plant is toxic if eaten, and it affects the brain, nervous system, and neuromuscular junction.

Symptoms of Hemlock poisoning include:

- Muscle tremors

- Salivation

- Lack of coordination

- Respiration rate increase

- Symptoms of colic

- Seizures

- Dilated pupils

- Breathing difficulties

Red Maple

While red maple trees are beautiful, they are not safe for horses. Horses are at most risk during the fall or after stormy weather that brings leaves down from the trees.

Dying or wilted leaves contain a toxin that attacks red blood cells when eaten, which causes severe anemia and the loss of the blood’s oxygen-carrying ability. As little as 1.5 lbs of eaten leaves can cause severe poisoning. The toxin has yet to be identified.

Early detection and veterinary treatment can, in some cases, save the horse from death. Prevention is the best policy!

Symptoms occur from 18 hours to 5 days after the horse has eaten the leaves. They can include:

- Weakness

- Dark brown or red urine

- Depression

- Lack of appetite

- Yellow mucus membranes

- Increased heart rate

Water Hemlock

Like Poison Hemlock, Water Hemlock is often fatal. If a horse survives past eight hours without the added complication of seizures, it has a better chance of surviving.

Water Hemlock’s most concentrated area of toxin is in its roots. It tends to grow in wet areas, and it is easy for horses to pull up and access the roots.

It is common for signs of poisoning to go unnoticed, and sadly many horses that ingest it are found dead. Subtle signs include twitching in muscles and around the face. Seizures can then follow.

If you suspect a plant is any kind of hemlock, be extra careful when removing it. Wear gloves and don’t inhale it.

Yew

All parts of the Yew tree are extremely toxic for horses, and eating just a small amount is fatal. According to Rossdale’s equine vets, it can kill a horse in just 5 minutes after they eat it!

It contains two highly dangerous alkaloids – taxine A and B. There is no treatment or cure. Yew kills very fast. Signs of yew poisoning can include loss of coordination, breathing difficulty, and muscle trembling.

Often the horse will experience sudden death, with many horses found with the plant still in their mouth.

Don’t let this plant anywhere near your horses!

Bracken Fern

While toxic, a horse needs to eat a bigger quantity of the plant over a couple of months. Most horses won’t eat it as they don’t like the taste. However, the odd horse will really like it.

Signs of bracken fern poisoning are neurological. They can include muscle spasms, stumbling/staggering, circling, and seizures.

Thankfully, if caught early enough, the horse can be treated with thiamine by the vet. The best practice is to remove it from your land if you see it.

Avocado

Avocados contain persin, which is toxic to horses. Poisoning can present with several different symptoms, including:

- colic

- breathing difficulty

- heart rhythm irregularity

- swelling around the face

- neurologic dysfunction

All parts, the fruit, stems, and leaves, are toxic. Ingesting even a tiny amount is fatal. Stick to carrots and apples, and never feed a horse avocado.

Oleander

Oleander is fatal if eaten by horses. Just of note, it is also toxic to other animals and people. Death happens fairly quickly, within 8 to 10 hours. The component of the plant that causes poisoning is oleandrin. This will cause cardiac arrhythmia.

Only a handful of ingested leaves can cause death but the entire plant is poisonous.

Yellow Star Thistle

Yellow Star Thistle is also known as golden starthistle, St. Barnaby’s thistle, yellow cockspur, and cotton-tip thistle.

It is an invasive non-native plant found mostly in the western half of the US, south-central Europe. The Middle East, and Asia Minor.

It causes what is known as ‘chewing disease’ in horses. This disease is also caused by horses ingesting a similar plant called Russian knapweed.

It is a neurotoxin, most likely repin. However, the exact toxin is yet to be discovered. Poisoning builds up over time with repeated ingestion until the toxicity threshold is reached. The toxin builds up in the brain and causes neural tissue.

Symptoms include:

- Anxiousness

- Confusion

- Difficulty eating and drinking

- Hypertonicity of muzzle muscles

- Tongue hanging out

- Constant chewing motions

As the disease progresses horses suffer muscle paralysis which prevents them from eating and drinking properly. The neurological damage is not treatable and euthanasia is the humane option.

Johnsongrass

Johnsongrass causes cyanide poisoning, teratogenesis, and neuropathy. Horses that ingest Johnsongrass are more likely to suffer teratogenesis and neuropathy than cyanide poisoning.

Poisoning occurs over a few weeks.

Symptoms include:

- Ataxia

- Lack of coordination

- Urine dribbling

- Hind leg and tail paralysis

- Abortion in pregnant mares

Not all horses are affected by eating this plant. The toxicity threshold is not fully understood. While not always fatal, horses have a poor prognosis, especially if nerve damage has occurred. If signs are noticed before serious nerve damage occurs the vet may be able to help the horse.

It is best to prevent this plant from infiltrating your land and hay to avoid any risks.

Locoweed

The entire locoweed plant is toxic to horses. The component associated with this plant that causes neurotoxicity is swainsonine. It also goes by the name Lambert’s crazy weed. Many horses find it palatable.

Symptoms include:

- Ataxia

- Congenital defects in foals or fetal death

- Temperament changes

- Depression

- Difficulty standing

- Unpredictable dangerous behavior

Often stopping horses from eating the plant can result in recovery but any nervous system damage is permanent. However, once horses get a taste for the plant they will seek it out.

Milkweed

Milkweed is usually not a plant that horses will avoid when grazing or if it makes its way into their hay. The toxins include a neurotoxin and cardiac glycoside.

It is often fatal and horses usually die within 24 to 72 hours.

Symptoms include:

- Colic

- Seizures

- Lack of coordination

- Irregular heartbeat

- Pupil dilation

- Lethargy

If poisoning is caught quickly enough, a vet may be able to save the horse. Always ensure your hay is from a reputable source, as many cases arise from milkweed-contaminated hay.

For more information on how you can become an Equine Osteopath, click here

It’s important to treat early as mud fever can lead to worse infection, such as cellulitis, which can be very dangerous.

It’s important to treat early as mud fever can lead to worse infection, such as cellulitis, which can be very dangerous.